Introduction

When I first began writing this post, my original intention was to present and evaluate some proposed ring structures in sūra Yūsuf as a part of my series on this sūra. However, when doing some preliminary reading on the topic— mainly on objective criteria about what makes a ring, I realized that the concept is often applied quite loosely. This post is going to be focusing on some of my early (and very brief) impressions of what rings are, and examples of what they are not.

So what are ring structures? These textual structures are an organizing principle where the first half of a text matches the second half in reverse order. This matching is usually on the grounds of style, literary features, content or themes and so on. The result of this principle is that the text ends up looking a lot like concentric rings (hence the name). A small example from the “Verse of the Throne” (ayat al-Kursī— Qurʾān 2:255) is shown below:

| A. Allah— there is no God but Him, He is the Living, the Sustaining. |

| B. Neither tiredness nor sleep overtakes him. |

| C. He owns what is in the heavens and the earth. |

| D. Who could possibly intercede with Him except by His permission? |

| E. He knows what is before them and what is after them. |

| D’. And they do not encompass anything from His knowledge except what He wills. |

| C’. His throne encompasses the heavens and the earth. |

| B’. Their preservation does not exhaust him. |

| A’. He is the Hearing, the Knowing. |

All elements in the first half of this ring have a close match in the second half. Sometimes the matching is on the basis of repetitions of phrase— for example, unit C ends with “the heavens and the earth” (al-samawāt wa-al-ardh), and unit C’ ends with the same formula. Other units of this ring match with their counterparts on a content or thematic basis— A and A’ match each other because they both contain two names of God. B and B’ match each other because they speak about God’s unending tirelessness, and so on. The ring has a central element that does not have any clear counterpart in any of the other units.

I chose this example because I don’t think anyone would deny that it exhibits a ring structure. Unfortunately, many proposed examples of ring structures are rarely this clear, and are often downright unconvincing. There is a tendency in scholarship on ring structures to simply exaggerate correspondence and try to read symmetry into the text when it is not there. In this next section I’m going to have a very brief look at some less convincing examples from both Qurʾānic and biblical scholarship.

A Not-So-Convincing Qurʾānic Ring

Over the past decade or two, ring structures in the Qurʾan have started gaining some attention from various scholarly circles. Some scholars (Michel Cuypers, Raymond Farrin, and others) have suggested that entire sūras follow this organisational principle, even finding evidence for consecutive smaller rings within one, larger ring represented by the sura as a whole. From my overview of these arguments, the quality of the proposed evidence for each case is quite disparate. Some analyses were quite clear and convincing to me, while others seemed quite forced. The main problem with the weaker arguments for ring structures was that there was simply a lack of any objective or obvious markers that should tie one unit with another. Scholars wanting to see a ring structure simply remedied this by stressing similarities between proposed units that were too vague or generic to be convincing. Consequently, Nicolai Sinai writes that:

“A reader who is not already invested in the validity of the ring-compositional approach will, upon suitably careful scrutiny, have reason to doubt many of the structural analyses put forward by both Cuypers and Farrin.”

Sinai, Nicolai. “Review Essay: ‘Going Round in Circles.’” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 19, no. 2 (2017): 106–22.

I would agree with Sinai that some of the analysis in both Cuyper’s and Farrin’s respective books are pretty fast and loose. A lot of the time the correspondence between two supposedly matching units in their presented rings are pretty generic. To give one example, take Cuyper’s analysis of Q5:2—

Source: Cuypers, Michel. The Composition of the Qur’an: Rhetorical Analysis. London ; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2015, 107.

I can’t really grasp most of the correspondences suggested above. What is the link between A(2a) and A’(2l, m)? Cuypers suggests:

At either end, the counterpart to the call to the believers (A) is the theological formula (A’), ‘fear God’ (l); ‘fear God’ … is almost an equivalent to ‘believe’.

Here he cites Izutsu’s Ethico-religious Concepts in the Qurʾān. Cuypers is actually referring to Izutsu’s observation that fear (or taqwā) of God is integral to being a believer. Although this may be true, Cuypers equivocating the two is a gross exaggeration. After all, there are many things that are integral to being a Qurʾānic believer— such as calling on God, following His commands, believing in the afterlife, doing good, et cetera. Whatever the case, this seems too generic a correspondence to justify putting “oh you who believe…” with “fear God!”. Similar can be said for his linking of the members C and C’— Why does 2e “seek favour from their Lord and satisfaction” go with 2g “And let [not] hatred of people…”? I reproduce Cuyper’s answer to this without comment, as I believe the reader can quickly see the forced nature of the analysis:

‘The favour of their Lord’, object of the desire of every pilgrim in C, is opposed by ‘the hatred [of the Muslims] for a people’, the object of the fear of this people in C’.

Cuypers, Michel. The Composition of the Qur’an: Rhetorical Analysis. London ; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2015, 106.

This is not to say that all of Cuyper’s analysis is wishy-washy, and I was actually convinced by several of his suggestions, as well as some other structures posited by other scholars— I have already provided one example in ayat al-Kursī. I think it’s important to have a set criteria in mind that can be followed so we can avoid positing really generic relationships like the above example in sūra al-Māʾida. Before I get to more examples of convincing Qurʾānic rings, I would like to go on a brief tangent on ring structure scholarship outside Qurʾānic studies, which I think suffers from much of the same problems Cuyper’s example has highlighted.

Not-so-convincing Biblical Rings

Just as with many other trends in western Qurʾānic scholarship, the practice of spotting and analyzing ring structures within texts takes its precedence from the field of biblical studies. A notable study in this category is Mary Douglas’ Thinking in Circles, a rather popular book on ring structures in the bible and ancient literature. This book often gets cited in the opening sections of much of Qurʾānic ring literature.

In this book, Douglas attempts to lay down some rules for what ring structures are (and aren’t), as well as providing some anthropological background to how they might have arisen and why they aren’t used any more. The meat of the book is some worked examples from ancient literature, most notably the bible.

I can’t find any critical reviews of Douglas, but what really struck me was how unconvincing most of her examples were (her flowery prose did not help in clarifying them either). I shall provide a few examples:

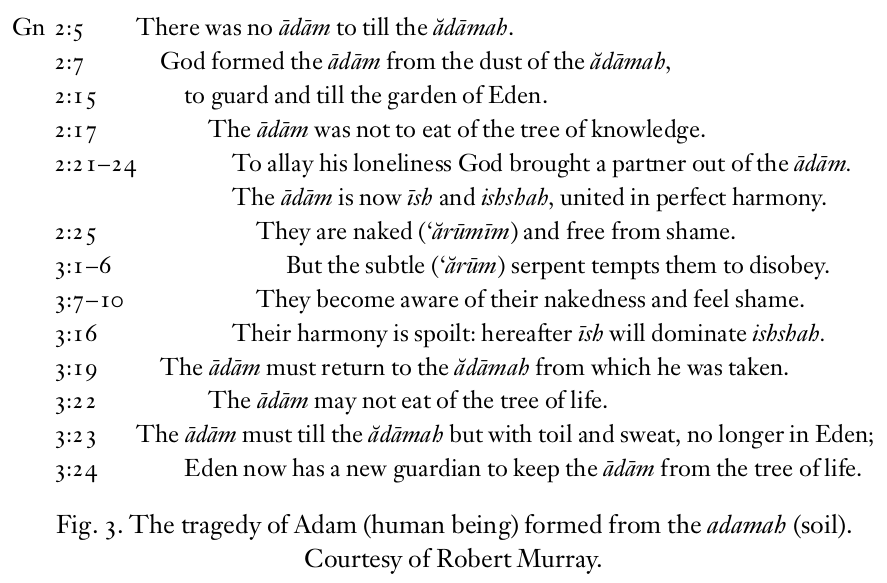

The “Tragedy of Adam”

This example actually seems convincing at first sight, until one notices that the structure ignores many of the intervening passages in Genesis 2-3. Murray (who Douglas is citing here) builds the ring by mapping the repetition of the word ādām (man / earth) and some other ‘key words’ in Genesis 2:3, which would mean that any passages not containing these words are ignored. This already dubious choice is invalidated when the above structure ignores some of the verses where these words do occur(!). For example, why ignore the occurrence of ādām in v. 2:16, 3:8, 12, 17 and many other intervening verses? I don’t understand the methodological basis of this analysis. Douglas, ironically, follows up with this comment:

It is a lesson to teach us to expect subtle sophistication and to realize how much we miss in the Bible when we try to read the apparently simple stories without knowing the sounds of the Hebrew words.

Mary Douglas, Thinking in Circles: An Essay on Ring Composition, Terry Lecture Series (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p 15.

Let’s look at an example that fares a little better:

The Akedah Ring

Douglas goes on to provide another example— Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis 22:1-18. I’m a little more convinced of her analysis here but I will say it is quite loose. Let me explain why.

This ring kind of works because Douglas focuses on repetitions of phrase to tie segments together. For example, sections v. 2 and v. 15-18 are tied together by God’s saying “your son, your only son” (ʾet-benkhā, ʾet-yekhīdkhā ʾasher); v. 7-8 are tied to v. 13 as they speak of burnt offering. There are also some thematic links between the segments: v. 3-6 and v. 14 ostensibly have something to do with the place they are going to. What is omitted from the figure above is the middle of the ring, v. 9-12, but a reading of this story would show it is a sort of ‘turning point’ for the whole episode— it is at this point God saves Isaac and everything turns out for the better. Such turning points often function as ring centres in narratives (such as in the Joseph story in the Qurʾān). Overall, the above structure does seem loosely chiastic.

However, Douglas’ analysis still suffers from the selectiveness that was so pervasive in the previous example of Adam’s fall. v. 17-18 don’t really seem to correlate with v.2 but are linked anyway, and the word ʿolāh (“burnt offering”) occurs six times in the passage but Douglas only notes them when they are relevant to her proposed ring (v. 7-8 / v. 13). If the burnt sacrifice is a plot device used throughout the story, then it’s likely that its occurrence in v. 7-8 and later on in the episode in v. 13 is simply coincidental. Singling out two specific instances of the word to conveniently tie together passages we want to lump together does not make for convincing analysis. I could poke some more holes here, but overall I’m willing to admit that the story could be a ring; just not a very ‘tight’ one like the Verse of the Throne and many other Qurʾānic rings.

More Convincing Qurʾānic Rings

All in all I’m not really impressed by most of Douglas’ book. The Akedah ring above was probably her most convincing biblical example. Things get very loose when she proposes that the entire book of Numbers exhibits a ring structure. If biblical rings are the standard, I think scholars have a much easier time finding rings within the Qurʾān than within the bible, assuming that Douglas’ book is representative of the literature on the topic (NB: If anyone has more convincing examples of biblical rings, please share them in the comments below).

To conclude this post, we’re look at some other examples of rings in the Qurʾān I find convincing. These examples come from Sharif Randhawa and Nouman Ali Khan’s Divine Speech. I really consider this book a cut above the rest, as the thematic links between ring sections generally aren’t forced, and are often supported by textual markers (phrase repetition for example).

Adam and the Angels

One of the more interesting chapters in Divine Speech puts forward the thesis that sūra al-Baqara (Chapter 2 of the Qurʾān) is composed of a large number of smaller, consecutive rings. In turn, these rings are also tied to each other such that the entire sūra exhibits a “rings within rings” structure. I haven’t yet evaluated whether this macro-structure holds up, but the individual consecutive rings themselves are mostly convincing (with exceptions of course). Here is one example from 2:30-34 (bracketed key words my own):

| A. God announces to the angels that He will create a vicegerent (Adam) (30a). |

| B. The angels question; God responds, “I know (innī aʿlamu) what you do not know” (30b). |

| C. God teaches Adam all the names (al-asmāʾ); the angels are commanded to inform of them if they can (31). |

| D. The angels confess, “Exalted are you! We have no knowledge except what You taught us. Indeed it is You who are the Knowing, the Wise” (32). |

| C’. Adam informs the angels of the names (al-asmāʾ) (33a). |

| B’. God says to the angels, “Did I not tell you I know (innī aʿlamu) the unseen of the heavens and the earth? And I know (aʿlamu) what you manifest and what you have concealed” (33b). |

| A’. God commands the angels to prostrate to Adam (34a). |

Most of the key correspondences here are pretty obvious— for example, B and B’ are tied together by the key theme of God’s knowledge, and God’s answer to the angels’ questioning in B is effectively repeated and reaffirmed in B’. C and C’ are obviously counterparts— God teaches Adam the names of things and challenges the angels to speak them in C; while in C’ God commands Adam to tell the angels their names. Element D is a fitting center of the ring given its powerful proclamation of God’s knowledge. A and A’ are less clearly linked. The correspondence between Adam being a ‘vicegerent’ (khalīfah) and the angels bowing to him isn’t immediately obvious, though I suppose a loose similarity on the basis of amplifying Adam’s greatness could be the common factor.

The only element that really sticks out to me here is the angels’ question to God in B (i.e. the middle part of verse 2:30) which does not have a clear correspondence in any of the later units. I suppose we can insist that the angels’ questioning can be subsumed into the theme of God knowing better, which is fine if we accept this ring is a little looser than what could be. Nonetheless, it’s still definitely a ring, and I would rate the strictness of the composition as somewhere between our ayat al-Kursī example and the biblical akedah ring. I used this example because I see it as a “typical” ring in sūra al-Baqara (which is practically built from such rings); it’s not an absolutely symmetric example but it’s chiastic enough to be recognizably a ring.

Light upon Light

Let us now turn to a more famous passage— the “Verse of Light” (Q24:35)— again from Divine Speech:

| A. God is the light of the heavens and the earth. |

| B. The example of His light is like a niche in which there is a lamp. The lamp is in a glass, the glass as if it were a brilliant star. |

| C. [The lamp] is lit from a blessed olive tree |

| D. neither of the east |

| D’ nor of the west. |

| C.’ Its oil almost radiates even though a fire had not touched it. |

| B.’ Light upon light. |

| A.’ God guides to His light whomever He wills. |

This example is highly symmetric, like the previous case of ayat al-Kursī. Each of the sections have an undeniable link to each other that they do not share with the other segments— our loosest correspondence, A and A’, are statements about God being and guiding to light, while all the other inner segments describe the light itself. B is a lengthy section on the layers of God’s light, aptly matching “light upon light” in B’. C and C’ describe the oil which the (metaphorical) lamp is lit from; and D and D’ perfectly mirror each other in almost every way. There’s not much more to this example— it’s a good example of a very tightly bound Qurʾānic ring.

Concluding Comments

In this post, we had a look at about ~6 proposed rings; two of these were biblical, and four were Qurʾanic. The biblical rings didn’t fare very well, as they either seemed non-existent or extremely loose. I didn’t choose these on purpose, so if anyone has any examples of tighter or more convincing rings of moderate length (i.e. a few verses) in the bible, please point me to them!

Of the four Qurʾānic rings, we saw two that were very obvious, one that was very likely to be a ring but somewhat loose, and one that was an example of not a ring. My takeaway is that Qurʾanic rings definitely do exist, but I think people should be careful before flaunting intricate Qurʾānic (or biblical) rings. It pays off to actually sit down and read the analysis yourself, rather than sharing around impressive looking tables and figures and claiming “intricacy!”.

In my next post, I shall return to my series on sūra Yūsuf, exploring the question of whether whole sūras exhibit a larger ring structure. This will be by far the biggest ring that we’ll look at, and it would be very interesting to see whether recent studies hold up.

As-salaam ‘alaykum,

First, it’s always nice to read your posts. Been loving the last couple in particular.

On this specific post, I wanted to ask if you’d seen my work over at heavenlyorder.substack.com? I’m trying to compile all research (much of it my own) on the structure and cohesion of the Quran. It’s not all ring structures tho. Some of it is parallel too.

Reason I ask is because I’m actually looking for someone with a critical eye to review them. Would love for you to read some and let me know what you think.

On Surah Yusuf in particular, I published my own research on it, in addition to what has been done by Jawad and NAK. Insha’Allah you’ve seen that and plan to discuss it.

https://heavenlyorder.substack.com/p/surah-yusuf-new-research

BarakAllah feek

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for informing me! I had heard of this but I didn’t know you were looking at sūra Yusuf. I was going to mostly assess Jawad’s paper but I’ll have a close look at your study too.

LikeLike

Assalamualaikum akhi can you respond to the claim that the Quranic challenge has been met by virtue of the fact that it quotes the words of people, Men and Jinn alike? I recommend watching the following…..

LikeLike

Assalamualaikum can you refute the following…..

https://www.thetorah.com/article/does-ishmael-molest-isaac

LikeLike

Asalamualaikum Wa Rahmatullahi Wa Barakatahu,

Recently you have said that you have been doing some research on new projects. I was wondering if you had been doing any research pertaining to Deuteronomy 33:2. Many early exegetes of the Qu’ran connected Surah 95:1-3 to Deuteronomy 33:2, such ibn taymiyah, ibn kathir, ibn qutayba, samuel al maghribi. Do you think their connection has any weight.

“By the fig and the olive. By By Mount Sinai. And by this secure city”

They would say the fig and olive corresponds to the region of Judea where Jesus(as) preached. Mount Sinai corresponds to Musa(as) where Musa(as) preached and the secure city refers to Makkah.

Likewise in Deuteronomy 33:2 we read

““The Lord came from Sinai and dawned over them from Seir; he shone forth from Mount Paran. He came with[a] myriads of holy ones from the south, from his mountain slopes.”

Intrestingly there are pre-islamic exegetes that say this refers to God giving revelation to people from Edom, then giving revelation to the Arabs, but both of them rejecting it and so the torah was given to the people of Sinai.

https://www.academia.edu/27035464/_Tracing_Possible_Jewish_Influence_on_a_Common_Islamic_Commentary_on_Deuteronomy_33_2_Journal_of_Jewish_Studies_67_2_2016_291_304

LikeLike

The places would be connected, not the Surah itself.

The Arabs would call a certain place, by a feature common to it. In the case of Figs, it refers to Mount Judi most likely, meaning where the Ark rested.

In the case of Olives, it refers to the Mount of Olives, where Jesus prayed and the fig passed away from the Israelites and to the new kingdom,

Mount Sinai represents the place where Moses had the Israelites received the Torah,

The Sacred Valley refers to the place the Descendants of Ismael received the Quran.

The first two places represent the concept of punishment, while the latter two places of reward, giving wait to the thesis there follows, which is the eventual Accountability.

The same symbolism applies to the prophecy of Deuteronomy, in the Seir refers to the place of Jesus, Sinai refers to Moses and Paran refers to Muhammad.

Whether or not the pre-Islamic exegetes took it different is irrelevant, especially considering their lies regarding the coming of the Prophet (S) and their trying to paint Ishmael (AS) and his descendants in a negative light.

The reality is the complete manifestation of the prophecy, where it SHINES and the Lord descends with his 10000 Saints occurs at Paran, which refers to the Prophet and His Companions conquering Makkah and the Baitullah. He (S) was the awaited One. Even the Book of Haggai states the Prophet like unto Moses would DESCEND, not ascend upon the Temple.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jazakallah khair for your response I was wondering if you knew of anyway to connect seir to Isa(as)? As far as I’m aware I was able to find nothing to connect the region of Seir(Edom) to Isa(as) or the region of Figs and Olives.

There does seem to be a mention of some people from Edom comming to witness Jesus’s miracles but it just seems to be mentioned alongside other places not anything particularly connected to Jesus(as)

LikeLike

1. The first thing one should realize when dealing with these type of prophecies is that tendency if the “scribes of Israel” to lie. For example, although the OT references the name Isaac (AS) as part of the sacrifice, this is a clear interpolation that multiple passages, as well as Chapters, very well prove beyond reasonable doubt. If one proceeds from the ‘de facto’ premise the scribes were being completely faithful to the tradition, particularly as it relates to Ishmael (AS) and the Arabs just being granted a secular existence, they would render themselves in complete confusion, because it’s “blind leading the blind”.

All the ‘academic’ papers can never rectify these fundamental facts. The scribes of the Israelites patently lied, as the internal evidence indicates. The earlier one accepts these realities, the less one wastes time.

2. Even prior to this statement, in Chapter 32, it ends with a blasphemies insertion, which stated the reason why Moses (AS) and Aaron (AS) couldn’t enter into the Holy Land, but the Israelites could, is because the two glorious Prophets (AS) disobeyed God, multiple times. God curse the hand of the scribes that inserted this filth. They didn’t even spare the father of their nation, Moses (AS), let alone the Unlettered Prophet (AS) or Ishmael (AS) in their own book, when it came to their tribal interests and propping up themselves as an ethnic group, and not a people bestowed a momentous obligation to witness the truth of God to mankind even on a political plane.

3. It is this blasphemous passage that introduces the prophecy in Deuteronomy. Now I would NOT necessarily argue it has to do with any Prophetic personality per say, but the whole Prophetic phenomenon as regards to the lands that were promised to Abraham (As) and his Descendants. This is in reality what is stated in Deuteronomy 34, which once again evidences the interpolations of the scribe.

A. As far as interpolation, 34 placed the viewing of the Hold Land in this context, which completely contradicts the ‘section’ in Deuteronomy 32, of why Moses can’t enter the Holy Land. 34 doesn’t stain the personalities of Moses and Aaron, but grants Moses the highest praise and grandeur. This distinction between 32 and 34 is one the types of ‘tahrif’ the Quran mentions regarding the Israelites and the Torah. This is even more evident in the sacrifice incident and events around Abraham (AS) which are actually in the Hijaz.

B. In Chapter 34, Moses (AS) is shown the lands God in promised to Abraham and his Descendants. Now as a Muslim and as even the OT clearly establishes despite the interpolations, the lands included the lineage of BOTH of the descendants of Abraham (AS). The images of the Prophecy is that of the Lord leading his army, moving from Sinai, THROUGH Seir and into Paran, which is region of the Hijaz and where Ishmael (As) was settled to be the custodian of the Baitullah. So the prophecy is not about the revelation per say, but the bestowal of the area God granted to Ibraheem (AS) and his Descendants to witness the truth as nations for the rest of humanity of which revelation is part and of which a NEW LAW, via a Prophet like unto Moses, would be given.

Again, the main prophecy is the army of God moving from the West to the East to fulfill the promise of God to Abraham (AS), the fulfillment ending in the liberation of the original Temple established for mankind, the Kaaba. This was and is the main center of the Abrahamic movement. One must understand that with Abraham (AS) the revelational phenomenon became INTERNATIONAL, and part of this was the granting of certain areas as part of this covenant. It is from here that a certain divine law came into play regarding the nations of these Blessed Personalities.

4. So if one proceeds from the premise that Isaac was the only heir to the legacy of Abraham (AS) and the scribes were ‘playing fair’, the reality is one will be a fool, period. You will be waiting for a “Messiah” that will never come, because the Awaited One, fulfilled the prophecies. There is no sugar coating this.

5. Don’t conflate Surah Teen with this prophecy, outside the ‘religious symbolism’ they employ. Surah Teen operates on its own fundamental thesis, which is the events tied to these places give specific proof of the Day of Judgment.

LikeLike

I also think, from the literary perspective, the “rising of God” as He proceeds from the West, in Sinai, eastward through what is the Sinai Peninsula, meaning Seir, into the Hijaz, is painter in direct contrast to the normal phenomenon of the sin, which rises from the East to West.

It’s almost as if the whole phenomenon is unexpected and sudden, completely unique. Remember, this is an area of countless pagan Empires, fighting over territory which is the most geographically strategic area in the whole world, providing access to three major continents. Their ‘kings and queens’ claimed right to rule, via divine heredity. The movement of the Lord will manifest in all its glory, suddenly, when He descended upon His Temple.

Further, the Prophetic phenomenon, particularly through Abraham (AS) and His Descendants, built on Tawheed proclaims God Almighty has no such parallel and no children to inherit or even share in His Rule. The Messengers are slaves of His, bound by the same law or Shareeah as the rest of Humanity, minus certain obligations thar pertain to the Risalah specifically, of which are actually more indicative of the momentous responsibility they bore. The Prophet (S) for example, was REQUIRED to pray Tahajud, meaning be awake over half the night, pondering over the law and revelation granted to Him (S). Compare this to the ‘kings and queens’ living the lap of luxury. According to our tradition, even the exemplar of Kingly Rule per the Israelite tradition, David (AS), fasted pretty much almost every alternative day.

The liberation of the Kaaba, the House of God established by Ibraheem (AS) per Divine Order, was the central mission of the Prophet (S) and the Ten Thousand Saints, because it was the Center of this Spiritual Nation, which was granted to Abraham (AS) and His Descendants, and fulfill the promise God granted to mankind to the Spiritual Giant that is Ibraheem (AS). Unlike the world kings, Ibraheem (AS) was ready to sacrifice his own lineage and legacy, for God Almighty, in complete submission to Him. So one can only imagine what this event signifies of which the Quran calls “The Victory”. It is not a Temple of worldly kings and queens, it is the Temple of House of God, located in an arid region, of which only those who really thirst for the Real King would venture to bow down their heads in Reverence and in Fear and Hope.

What about unparalleled symbol for the return of “Kingdom of Heaven on Earth” that Jesus (AS) gave the Good New for!

And one can imagine what the prejudiced tribal Israelite priests, of whom became infatuated with the worldly goods, as is attested to all over the OT and NT, let alone Quran, were jealous of, such that they interpolated and interpolated and interpolated.

LikeLike

Yes, the way the scribes dispatch Moses from the story is testimony to the confused transmission process of these scriptures.

Towards the end of the Israelites’ wandering in the desert, they arrived and camped at the desert of Zin Numb20:1-13. As before, the Israelites longed for water so Moses was commanded to take his staff and, along with his brother Aaron go talk to a rock for it to produce water. Instead of talking to it, Moses struck it twice with his staff (the staff God had explicitly ordered him to take with him at the site), following the method that worked before, which caused an abundance of water to gush forth. Both Moses and Aaron are then forbidden from leading the Israelites to the promised land, a role now trusted to Joshua, Moses’ disciple. The reason for that divine decree is the source of much controversy in rabbinic writings, with many speculating on whether the forced relinquishing of their leadership to guide the Israelites to the promised land was directly linked to the striking of the rock instead of talking to it, or something else. After all God did tell him to take the rod with him, and water did gush from the rock as a direct consequence of being struck. Also, Aaron was equally punished yet he wasnt the one to have “disobeyed” the command by striking the rock instead of talking to it. Although the text clearly states that the events “at the rock” directly led to this divine decree, nowhere does the text explicitly define the cause that led to it. In fact the wide range of comments offered in traditional interpretive literature is so vast, from Moses committing no sin at all to a long list of transgressions that led to demoting him from his position, that most Jewish scholars loath to investigate the issue in depth, fearing to unjustly burden Moses with sins he might not have ever committed.

What clearly transpires is that, despite the obvious fact that the entire details of the exchanges at the rock werent completely reported, a conflict occurred there, like a rebellion “Moses said to them, “Listen, you rebels..” and the name of the place itself, Meribah, evokes quarelling. Both Moses and Aaron are depicted as having some leadership issues in the midst of that confusion -which isnt a sin- that could have been the most probable conditions to make them step down as the nation’s leaders, like their previously mentioned falling in prostration in public waiting for a command from God following the nation’s complaints, instead of honouring God’s name to their people by showing the kind of authority and initiative one would expect from leaders and prophets chosen and appointed by God.

An interesting anecdote in Muslim literature is that of Moses’ encounter with an angel of death. The angel, sent in human form was slapped by Moses so hard that his eye fell from its socket. Moses was a passionate man who many times physically expressed his inner frustrations, anger or fears. In sura kahf he contested the actions of an envoy from God despite the warnings not to interfere. But as when he punched a man in Egypt whom he thought was an unjust aggressor, or when he threw down the tablets of revelation, or when he violently seized his older brother and prophet Aaron’s beard following the incident of the golden calf, none of his actions were incited by base desires or sinful motives.

Maybe Moses in this case did not believe him to be God sent initially, just as Ibrahim and Lut did not originally know that their guests were angels. The unspecified circumstances of the encounter or the dialogue that occurred led Moses to do what he did. Add the fact that Moses had almost finally attained his life mission, after suffering over a 100 years of untold hardship, trials and frustrations, of having the promised land within reach.

This expressive man, who according to the HB was taken to God at the age of 120 while he still possessed all his strength and health Deut34:7 was certainly not going to let an unidentified visitor compromise his noble life goal, someone he most probably saw as a threat just as Ibrahim was originally fearful of his unanounced angelic visitors who came as humans 15:52.

But as he saw the same visitor a second time with his eye restaured he couldn’t dispute whatever the angelic envoy was saying, so he humbly accepted that his time had come, just as he always humbly returned to God following his outbursts 7:151,28:15-16. Moses declined God’s offer through the angel of having his years extended, preferring 100 times to meet his Lord right away in the everlasting abode than delaying it for a few more years in this ephemeral world “Allah restored his eye and said, “Go back and tell him (i.e. Moses) to place his hand over the back of an ox, for he will be allowed to live for a number of years equal to the number of hairs coming under his hand.” (So the angel came to him and told him the same). Then Moses asked, “O my Lord! What will be then?” He said, “Death will be then.” He said, “(Let it be) now.” He asked Allah that He bring him near the Sacred Land at a distance of a stone’s throw. Allah’s Messenger said, “Were I there I would show you the grave of Moses by the way near the red sand hill.”

This is the reality of Moses, the noble prophet’s dignified end. Neither did a mysterious sin lead to him being prevented entry to the promised land nor was God “furious” at him for some convoluted reason the judeo-christian scholars will never cease conjecturing about.

LikeLike